4n6ir.com

Compile Time Analysis of NotPetya

by James Habben

I had a thought the other day about some of the NotPetya / M.E.Doc (Medoc) initial infection vector that was released last week. I wondered if the attackers had full and complete access to the Medoc network and even source code. Did they have the ability to inject the malicious code into the source repository? Then just sit back while it got included into the build that was released to the customers. Or did they have more restrictive access to, say, the FTP server holding the update files?

Here are a couple references for those that didn’t keep up with the fast moving data related:

- https://www.welivesecurity.com/2017/07/04/analysis-of-telebots-cunning-backdoor

- http://blog.talosintelligence.com/2017/07/the-medoc-connection.html

I wanted to see if I had some data to support the level of access the attackers had, even though I don’t have access to the internal systems. It is very possible that Talos has already made this determination and just not made the statement public.

Executable (exe) and Dynamic Link Library (DLL) files have a timestamp in the PE header known as the compile time. This is often used to identify characteristics of attackers, as many times they forget to cover their tracks with this field.

In my inspection, it appears to me that the attackers had full and complete access inside the network with the ability to inject their malicious code into the source repository (whatever Medoc uses).

Single File

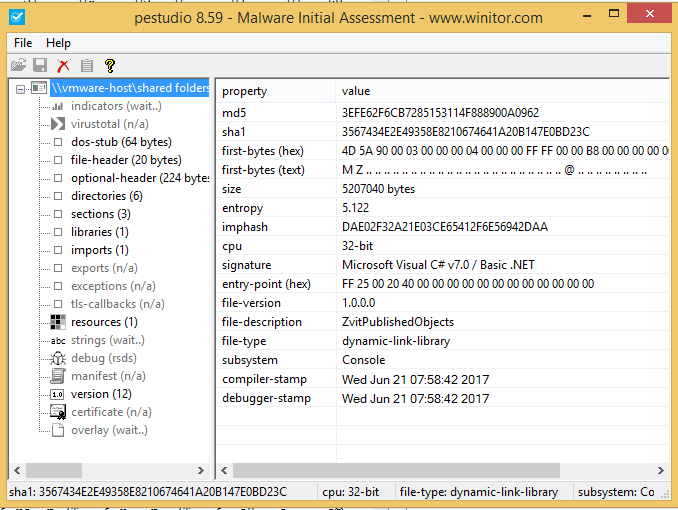

The first thing I did was use PEStudio to analyze the affect DLL file. The compile time in this view appeared to be within a normal time period based on other information that has been provided surrounding this attack.

The timestamp is shown in PT since my system has that set. The UTC time is 2017-06-21 14:58:42. I checked a couple other PE files and found it to be within the same time range.

Multiple Files

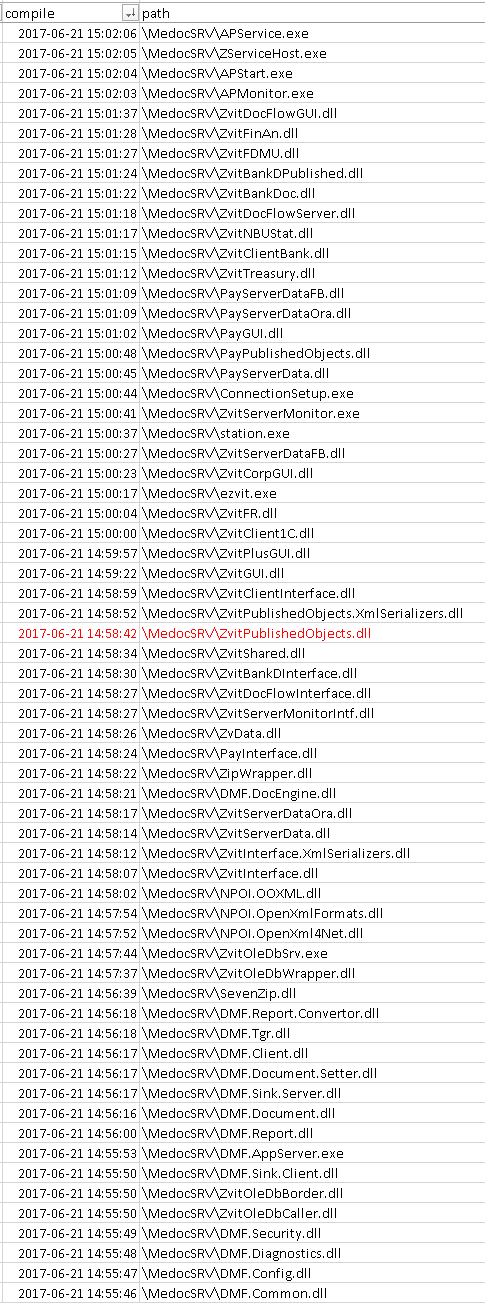

There are hundreds of files in the Medoc program folder and a large percentage of them are EXE or DLL. It makes no sense to check things one by one when we have the power of automation. Check out AdamB’s post on clustering analysis using compile times.

http://www.hexacorn.com/blog/2012/09/01/perfect-timestomping-a-k-a-finding-suspicious-pe-files-with-clustering

I took a similar approach and wrote up a quick EnScript to identify PE files and then parse the 4-byte compile time value and dump it out. I used this approach because EnCase allows me to analyze and extract data without having to mount or copy files out. Also, I have been writing EnScripts for a couple years. ;)

The result tells me that the attackers got the code injected at the source. Look in the following screen shot and you won’t find any times that are overlapping. It also appears to have a reasonable amount of time between files based on the sizes.

Unknown

What I can’t answer with my own analysis based on the data available is whether the attackers stole the source code and compiled it on their own. According to Talos, they had access to change the NGINX configurations to have the internal server proxy connections out to a server under their control. Did the attackers inject the code into the internal repository? Did the attackers steal the source code and compile it outside of the Medoc network?

Hope you found this as a nice little interesting tangent from your daily tasks. i did!

James Habben

tags: Timeline